Hakkaisan Snow Aged Junmai Ginjo 3 Years

Aging sake can be a tricky business. If not done skillfully, sake can turn stale and bitter tasting with age. If done well, aging sake can concentrate flavors and enrich and deepen the best traits of a sake. Hakkaisan uses two ways to achieve richness and balance in their aged sake.

Snow Aging

First, Hakkaisan makes use of an abundant, local natural resource in aging their sake: snow! Hakkaisan Brewery is located in Minami Uonuma City, an area of Japan famous for heavy, deep snowfall in the winter months. Hakkaisan has harnessed the power of the snow by creating what is known as a “yuki muro” or snow storehouse. The Hakkaisan Yuki Muro is a large insulated room that contains a 1000 ton pile of snow placed next to 20 sake storage tanks. The sake is chilled in tank using the cold from the snow alone. No electricity at all is used for chilling the sake making this a very eco-friendly facility.

Inside the Yuki Muro Snow Storehouse.

This snow storage concept is not a new one and has been used for generations in snowy regions in Japan to refrigerate foods before electricity. The snow in Hakkaisan’s Yuki Muro never melts completely, even after a full year, and it is re-filled with fresh snow every February or March. The temperature is a steady 2-5°C (37-41°F) throughout the year – an important point as too much temperature variation can adversely impact sake as it ages. Being able to chill sake at a steady temperature without electricity has another advantage. In the case of power outage or natural disaster, the sake will continue to age properly with no impact to the temperature.

No Dilution

The other method used to create depth of flavor and richness is aging and bottling this sake as a genshu. Most sake is diluted with water after production to bring the alcohol percentage usually down to about 15.5%. By contrast, genshu is a style of sake that is undiluted with water, similar in concept to “cask strength” products in the world of whiskey. In the case of Hakkaisan Snow-Aged Junmai Ginjo 3 Years, the alcohol percentage is 17%. What are the advantages of genshu? As genshu sakes are higher in alcohol, they offer more body, weight and structure to the sake. This translates into the ability to pair genshu sakes with non traditional foods. The keyword here is Umami! Richer foods with lots of savory characteristics pair beautifully with this genshu sake. Pairing ideas along this vein include beef tenderloin, Mediterranean seafood and even liver paté. This genshu sake also has the heft to stand up to mildly spicy dishes as well, so please try this sake with black pepper chicken or beef curry.

The other method used to create depth of flavor and richness is aging and bottling this sake as a genshu. Most sake is diluted with water after production to bring the alcohol percentage usually down to about 15.5%. By contrast, genshu is a style of sake that is undiluted with water, similar in concept to “cask strength” products in the world of whiskey. In the case of Hakkaisan Snow-Aged Junmai Ginjo 3 Years, the alcohol percentage is 17%. What are the advantages of genshu? As genshu sakes are higher in alcohol, they offer more body, weight and structure to the sake. This translates into the ability to pair genshu sakes with non traditional foods. The keyword here is Umami! Richer foods with lots of savory characteristics pair beautifully with this genshu sake. Pairing ideas along this vein include beef tenderloin, Mediterranean seafood and even liver paté. This genshu sake also has the heft to stand up to mildly spicy dishes as well, so please try this sake with black pepper chicken or beef curry.

Tasting

Let’s look at the stats for Hakkaisan Snow-Aged Junmai Ginjo 3 Years.

- rice-polishing ratio: 50%

- Alcohol: 17.0%

- sake meter value: -1.0

- acidity: 1.5

- koji rice used: Yamadanishiki

- brewing rice used: Gohyakumangoku , Yukinosei

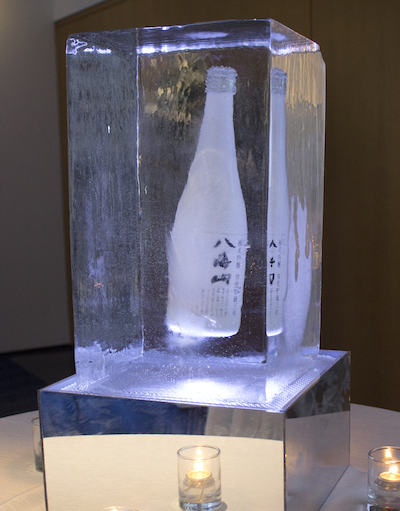

Hakkaisan Snow-Aged sake displayed in Ice.

Going International

Hakkaisan Snow-Aged Junmai Ginjo 3 Years was recently introduced to the USA with a a launch party at The Modern, the Michelin starred restaurant at the Museum of Modern Art in NYC. The event was attended by about 100 guests from New York restaurants and wine shops as well as press and VIP guests. Appetizers were passed for the group to try pairing this Snow-Aged Junmai Ginjo with non-Japanese cuisine. The President of Hakkaisan Brewery, Jiro Nagumo, was also on hand to introduce the sake to the attendees. It was noted that the beautiful all white bottle design is a reflection of the roots of snow storage used for this sake. You will soon see Hakkaisan Snow-Aged Junmai Ginjo 3 Years appearing in your local sake shops and restaurants. Please try this sake that is new to the USA – you can get a taste of Japan’s Snow Country in your town!

President Jiro Nagumo introduces Hakkaisan Snow-Aged Junmai Ginjo 3 Years to the guests at the sake launch Party at MoMA

Like so many things in Japanese culture, if you explore a little bit below the surface understanding of any topic, there is a whole world to discover… this is true for sushi, kimono and of course, sake, too.

Like so many things in Japanese culture, if you explore a little bit below the surface understanding of any topic, there is a whole world to discover… this is true for sushi, kimono and of course, sake, too.

The first step in making our own Shimenawa was to soften the rice straw to make it pliable. To this end, an an old fashioned press appeared from storage. this was a machine that looked like it had seen decades of Shimenawa production. A hand crank was turned and the rice fed through to crush it a bit and soften the fibers.

The first step in making our own Shimenawa was to soften the rice straw to make it pliable. To this end, an an old fashioned press appeared from storage. this was a machine that looked like it had seen decades of Shimenawa production. A hand crank was turned and the rice fed through to crush it a bit and soften the fibers.  After softening, the rice was brought into the work room and everyone sat down and started working. I first just watched and was amazed to see ropes and other woven decorations begin to appear.

After softening, the rice was brought into the work room and everyone sat down and started working. I first just watched and was amazed to see ropes and other woven decorations begin to appear. After a quick lesson, I was trying to make my own Shimenawa. My first two tries were a failure with my rope immediately unraveling, but after a bit more instruction, I figured out the trick and soon had a two ply thin rope of my own creation! I tied the rope into a circle to make a wreath.

After a quick lesson, I was trying to make my own Shimenawa. My first two tries were a failure with my rope immediately unraveling, but after a bit more instruction, I figured out the trick and soon had a two ply thin rope of my own creation! I tied the rope into a circle to make a wreath.

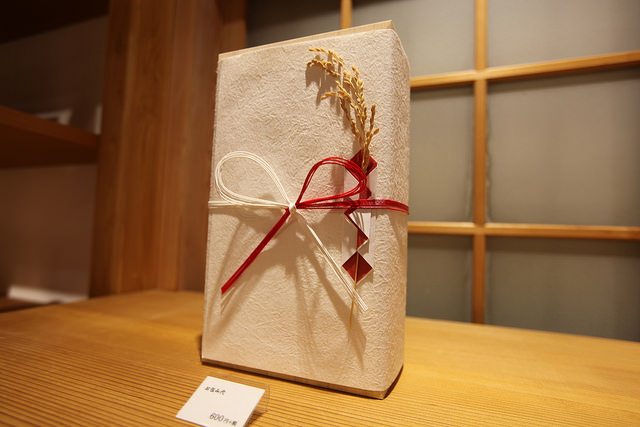

One of my favorite Japanese words that I’ve learned so far is gentei (限定), which simply means limited, but is often applied to a seasonal product or limited release product. Gentei items are popular in Japan! Hakkaisan also has some seasonal products, one of which is sold only in December each year.

One of my favorite Japanese words that I’ve learned so far is gentei (限定), which simply means limited, but is often applied to a seasonal product or limited release product. Gentei items are popular in Japan! Hakkaisan also has some seasonal products, one of which is sold only in December each year.

Almost every sake party or event I’ve been to in chilly Niigata has had someone assigned to be the Okanban. In short, the Okanban is the person in charge of warming sake. They make sure the sake is at the right temperature and ready when needed. At a busy event, it can be a lot to juggle, but a good Okanban keeps the sake and the party flowing!

Almost every sake party or event I’ve been to in chilly Niigata has had someone assigned to be the Okanban. In short, the Okanban is the person in charge of warming sake. They make sure the sake is at the right temperature and ready when needed. At a busy event, it can be a lot to juggle, but a good Okanban keeps the sake and the party flowing! The main tool of the okanban is the shukanki. This is a metal-lined wooden box that allows you to create a hot water bath inside for the sake carafes. A dial on the outside allows you to set the water temperature. This along with a good sake thermometer are what you need to get started.

The main tool of the okanban is the shukanki. This is a metal-lined wooden box that allows you to create a hot water bath inside for the sake carafes. A dial on the outside allows you to set the water temperature. This along with a good sake thermometer are what you need to get started.

After my arrival in Niigata, I was invited to visit the nearby Hakkaisan Son Jinja Shrine to join in a festival. The god of Hakkaisan Mountain is enshrined there and worshiped by locals. It sounded like a wonderful way to spend a fall afternoon. However, I started to worry a bit when I learned the festival was called “Hiwatari taisai “ or “walking on fire” festival.

After my arrival in Niigata, I was invited to visit the nearby Hakkaisan Son Jinja Shrine to join in a festival. The god of Hakkaisan Mountain is enshrined there and worshiped by locals. It sounded like a wonderful way to spend a fall afternoon. However, I started to worry a bit when I learned the festival was called “Hiwatari taisai “ or “walking on fire” festival.  I saw many festival goers walking around barefoot in preparation for the big event. After a beautiful procession of shinto priests, dignitaries and even an ogre (oni), the fire was lit. The flames were soon so high and the heat so intense that the crowd had to move back from the fence. When I saw the huge fire and billowing smoke, I began to question the sanity of the people lining up to walk on the coals, and I took a moment to re-confirm with myself that I would not be walking. When the fire died down, two paths were raked through the coals and sprinkled with salt to temper the heat.

I saw many festival goers walking around barefoot in preparation for the big event. After a beautiful procession of shinto priests, dignitaries and even an ogre (oni), the fire was lit. The flames were soon so high and the heat so intense that the crowd had to move back from the fence. When I saw the huge fire and billowing smoke, I began to question the sanity of the people lining up to walk on the coals, and I took a moment to re-confirm with myself that I would not be walking. When the fire died down, two paths were raked through the coals and sprinkled with salt to temper the heat.